Interactivity as Instrument. In the context of interactivity, the word instrument must be understood in both of its senses: at once as an object used to carry out or execute an action, and as a means of obtaining a result. On the one hand, interactivity allows for the manipulation of objects, actions, or configurations of functionalities. In this sense, it is the object itself — that which is manipulated — in order to produce an effect. But insofar as interactivity also encompasses the entire process by which this object is manipulated (cf. the program), one can say that interactivity is the means by which this object is manipulated — that is, the very event of manipulation itself. Interactivity is thus both the object being manipulated and the manipulation of the object. Here, object and context collapse into a single act.

Within the framework of computing, we can say that interactivity is simultaneously what I am able to do within a representational space (click here and there), and the more general experience of this “doing” (cleaning the “desktop,” drawing a duck). Why do these two dimensions tend to merge into a single word or concept that we call interactivity? The answer could come from many directions, but I would argue that it is because, in interactivity, one cannot understand functionality outside of its function. That is to say, within interactivity there is not even an object without its actualization in a context — more precisely, the context of the dispositif + interactor + program assemblage. The question at stake is: what is it doing there? An object cannot be understood outside of its relations to other objects, in relation to its own programming, and in relation to the overall figure drawn by the program as a whole. Interactivity is therefore an instrument: both the object of manipulation and the manipulation of that object.

Musical Instruments and Computational Instruments. This generalized notion of manipulation brings us to another important definition of instrument: the musical instrument. As with interactivity, a musical instrument cannot be understood outside of the broader context of its manipulation—that is, music. Music is both the context in which the instrument acquires meaning and the context produced by the instrument. For the instrument is, above all, a means of creation. It has its score, which in some sense resembles the program, and the capacity to transform that score, to actualize it, and to give rise to an entirely new event.

As with buttons, one of the most compelling questions for interactivity revolves around the following idea: What instruments should we create, and for what kind of music? From the moment one understands that, in computing, anything can become a button — text, image, sound — the button sheds its obligations to the logic of switches and frees its triggering function from its traditional constraints. One can then create a true keyboard of abstractions: an instrument that treats image, text, and sound as so many possible notes.

Images, Sound, and Gestural Instruments. When I take a digitized video image and introduce temporal manipulation of its time code, can we say that the image has become an instrument? An image-violin? This simultaneously transforms our conception of music and of the image. The answer is yes — but also depends on the broader capacities of the program to enable a form of “music” to emerge from its manipulation. In any case, the logic of abstraction and discretization means that any medium—sound, image, text, and so on—can be connected to, or even exchanged with, any other.

Using a digital guitar connected to a computer, for example, I can replace the synthesizer’s guitar sound with a recording of a poem by Amiri Baraka, allowing a musician to “play” the voice of the poem. The interest of such a dispositif—or of any dispositif that allows one to play images as instruments—is that it reintroduces the body and its gesture through the prosthesis. In doing so, it distances us from the cold interface that asks us to project ourselves into a symbolic space in order to perhaps encounter some affective substance there.

It is therefore unsurprising to learn that in the sixteenth century, the word instrument was most commonly used simply to refer to the various organs of the human body.

cf. accordage affectif, diagram, effort, prothesis

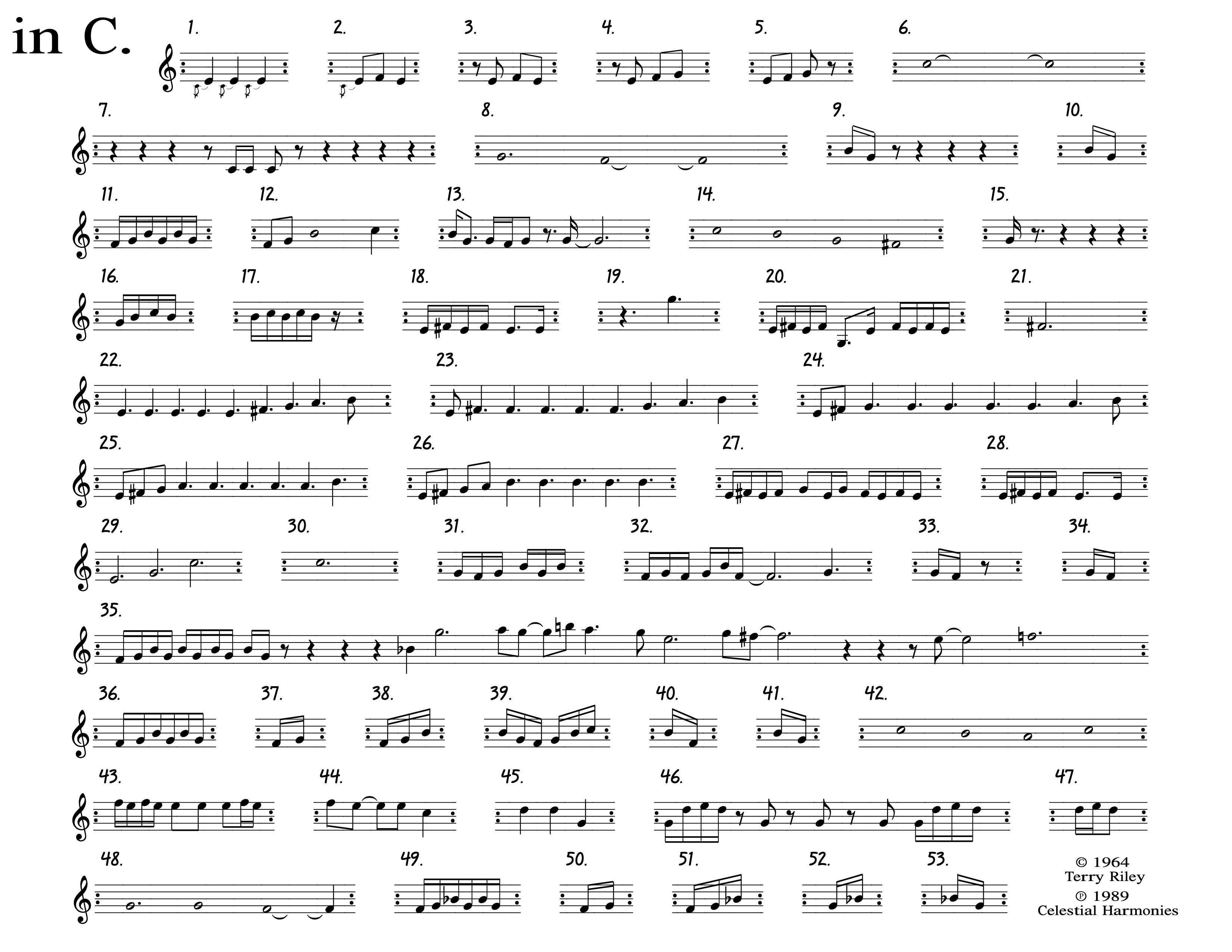

Written by Terry Riley in 1964, In c was an historical event that pointed the way to a future world of modular, algorithmically manipulatible, creation. Although John Cage had already dragged us kicking and screaming out of the classical mindset of composition through the introduction of chance into his compositions, it was In C that showed us what a successful algorithmically designed work of art could sound like.

At its most basic level, In C is a collection of what we today would call “loops” and which Riley described as “patterns”. The composition contains 53 of these short patterns which, Riley explained in his instructions accompagnying the score, “are to be played consecutively with each performer having the freedom to determine how many times he or she will repeat each pattern before moving on to the next.” The result is an evolving, changing, even mutating performance that is immediately recognizable to anyone who has heard it, and yet at each performance changes shape, based on the choices made by its performers.

It is almost comical how the concept of a simple musical loop has been integrated into contemporary performance and composition; in 1964 it was not the case. And while the composition inspired an entire movement — minimalism — it also paved the way for a musical form that would need a medium that itself was based on algorithmic technology, namely modular musical compositions that evolve while one experiences the work itself, as is the case in Generative Music in Video Games.

The work also contains a fundamental feature that can be heard in most modular works of this sort: time is itself a malleable, stretchable material, that the artist can work with. The work is not “a-temporal”; there is a specific cadence to the work, and the patterns are designed in such a way as to combine with each other in a sophisticated game of point-counterpoint: In C is an intricately composed work of temporal art. But this time can stretch, shift, an d even loop back over itself. It is a shifting sea of sands, no matter how recognisable its fundamental melodies.

- In C

- A Time For Foxes (2023)

- In C

- Michael Elder (2022)

EBN Video Sampler

Emergency Broadcast Network

Emergency Broadcast Network Video Sampler, EBN (Joshua Pearson, Gardner Post, Ron O'Donnel, Greg Deocampo).

Extending the process of “sampling” used in hip-hop, techno, and related musical genres, the Video Sampler developed by Emergency Broadcast Network makes it possible to play loops of video images as musical notes. Each audio-video loop is connected either to a MIDI electronic keyboard or to a graphical interface that allows each image to be triggered instantly and played in different ways: forwards, backwards, looped, or alternating between forward and reverse.

EBN’s Video Sampler is above all an instrument designed for EBN itself, since the group is essentially composed of musician-DJs who use the Video Sampler as a means of composing hip-hop and techno music.

Violin Power

Steina Vasulka

Together with her partner Woody, Steina Vasulka is known above all as one of the pioneers of video art. Before working with video images, she was a violinist, but she abandoned the violin in order to work with video. Rejecting the problems tied to image and representation, the Vasulkas never entirely abandoned the sound–image or music–image relationship, and instead went so far as to bring these domains together within their very conception of video:

“90% of people that developed video synthesizers had former interests in music. Each of their instruments at least contained circuits which were modulated by sound… All we were pointing to was the simple fact that sound could influence picture. Everything is defined simply by frequency, or voltage change in time in a wave form organization.”

— Interview with Woody Vasulka, Chris Hill

http://www.squeaky.org/sq/spring1995/sq_woody_vasulka.html

In the 1980s, Steina Vasulka returned to her original instrument, this time using an electronic MIDI violin capable of outputting computer data rather than sound vibrations. In a series of performances titled Violin Power, she connected it to a computer that allowed her to control a laserdisc of video images.

Personal Projects

CD-ROM projects:

la Revue virtuelle, Douglas Edric Stanley in collaboration with the Revue Virtuelle team;

La morsure, CD-ROM project by Douglas Edric Stanley with Andrea Davidson.

In several of my projects, I have attempted to offer a number of responses to the question of interactivity-as-instrument. This concern began primarily with the interactive sequences I designed for La Revue Virtuelle, where I discovered that the computer was capable of reading video images in its own way—and that this reading radically transformed the very temporality of the image.

I then developed a number of interactive sequences in which, starting from a suspended linear sequence, interactivity consisted in animating this sequence and unfolding the various possible readings of its image-movement. Through minimalist mouse gestures, the relationship between image, gesture, and instrument crystallized before my eyes.

The project La dernière heure takes up this dispositif by replacing the traditional mouse with a trackball, through which the user “caresses” the image and determines the frequency of image editing controlled by the narrative generator. The trackball becomes the instrument that sets the tone of the montage and indicates to the narrative generator—tasked with producing meaning from the images—the type of story it should construct.

The instrument is more than a simple means of manipulating image and sound: it is also the very articulation of the narrative, as well as the intrinsic movement of the image-movement itself.

With La morsure, this instrument–interactivity relationship takes shape through the image of the body. The gestes of the interactor are connected directly, or through deforming réflexion, to the recorded movements of dancers in order to construct an interactive choreography. Here, dance–music–body–instrument find a new expression through interactivity, as can be seen in the various examples already produced for the prototype, where a complex choreography must be unfolded as if it were a musical string to be played and replayed until its form is finally grasped.

This project, along with the project Lull, also introduces a more explicit relationship between interactivity and the musical instrument by creating reflets gestuels of sound. The sound must be unfolded through the intensive gestures of the interactor—it is up to them to “play” the soundtrack.

In Lull, it is the user’s entire body that takes on this role, using motion sensors that activate a voice in relation to the varied movements of exhibition visitors. It is the interactor’s body itself that serves as the instrument, with the computer functioning only as an extension of that instrument. The body assumes the role of an interactive prothèse and becomes itself a prosthetic instrument of the computer.