During a 3D training course, I decided to adapt Samuel Beckett’s Quad into an exhausting algorithmic loop of walking personas.

- Play: Quad

- Author: Samuel Beckett

- Adaptation: Douglas Edric Stanley

- Technologies: Blender, Unity game engine

- Process + Source code: abstractmachine/head-formation-blender

- Professeur : Claudy Iannone

- Trainee: Douglas Edric Stanley

- Formation : Modélisation, animation et rendu 3D. Introduction à Blender

- Dates : 2024.11.15 > 12.21

- Institution : HEAD – Genève

Project

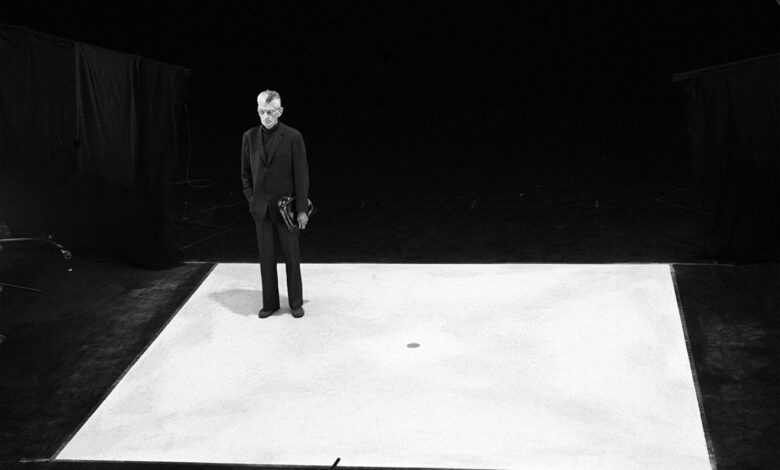

An adaptation of the television program Quad (play), written and directed by Samuel Beckett in 1981.

Adaptation

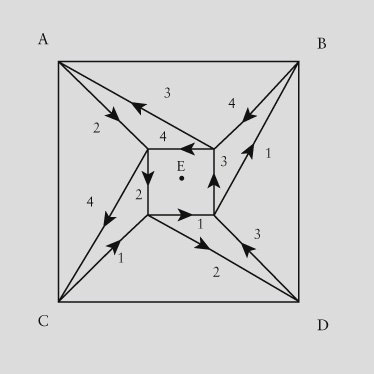

This project is an adaptation of the television play Quad, written and directed by Samuel Beckett for the Süddeutscher Rundfunk, on October 8, 1981. In this work, four characters of four different colors wander around a square, alternating their movements between approaching the center and moving away toward the four corners of the square. A rhythmic piece of music accompanies their wandering.

In this adaptation, I first modeled the four characters of the play in Blender. I then added an armature to these characters using Rigify. Finally, I animated their movements using Blender’s animation tools.

The result of all these steps was imported into Unity, where I controlled the characters’ movements through C# programming, rigorously following the diagrams written by Beckett in the original play.

The goal of this project was to gain a better understanding of the transition from 3D modeling in Blender to a final result inside a game engine, where characters are controlled in real time.

Quad

Quad is a television play by Samuel Beckett, written and first produced and broadcast in 1981. It first appeared in print in 1984 where the work is described as "[a] piece for four players, light and percussion" and has also been called a "ballet for four people." – Quad (play), Wikipedia

I & II

During filming, a variant — “Quadrat II” — was improvised on set by Beckett when he saw a control monitor used to calibrate cameras with a black-and-white image. In this version, the music and colors disappear, and the characters drag their feet laboriously. Beckett stated: “Between the two parts there is an intermission of 100'000 years”.

Diagram

Quad

Here are my theoretical notes on the play Quad, reflections, etc., which you can read in more detail in my notes on my process.

Videos

I have made available (unlisted) both versions of Quad in a higher resolution than what is usually found online:

First part

I read the first part of “L’épuisé” (Exhausted) by Deleuze. This first part constructs a kind of generalized reading of Beckett, distinguishing “the tired” from “the exhausted.” In the second part, he addresses Quad more directly, but in this first section Deleuze treats Beckett’s work as a whole, and especially those strange characters such as Molloy or Winnie buried up to her neck.

The central argument revolves around the idea of a work that attempts, through various strategies, to exhaust language, speech, image, and then space. Deleuze describes characters who are not simply lying down (= tired); rather, they are seated but immobilized.

The word that seems to haunt this text — and which Deleuze addresses and then sets aside, though with little insistence — is the question of silence. It is even the end of the text. Basically: how does one speak of silence in a text, in a play, in a film, in a television broadcast? From this perspective, it is close to Heidegger’s project: how can one speak of a deafening silence?

This question of silence is a way of addressing Beckett’s extreme purification, which is not minimalism. It is not an attempt to simplify meaning or representation; rather, it is a project to exhaust it through an internal movement.

Second part

The second part of Deleuze’s text deepens this question of a silence that can never be reached; or only through the detour of an exhaustion of meaning, of noise, of signal.

The project of the text seems to be a kind of treatise on art and its limits: how the work of a singular artist could internally surpass this dilemma of how a work can speak of an entity that does not pronounce its name, of a noise that emits no sound, of an object that produces no form, of an image that radiates no light. I.e. how to “exhaust” from within representation, the limits of representation.

It is in this sense that Deleuze speaks of exhaustion, and this is what brings it close to his definition of the refrain and the way animals use the repetition of territorial markings to exhaust a space: one goes around the space in all its corners; not in an exhaustive manner, but just enough to exhaust all potential dangers, unknowns, or unexpected events.

With animals, the concept of exhausting the possible is relatively easy to grasp: the animal attempts to exhaust all open vectors that could kill it, take its food, or steal its offspring. We say attempts, because the exercise is endless, yet one nevertheless seeks to finish once and for all, before being finished once and for all. This is what distinguishes it from what Deleuze calls “realization,” that is, work, labor, accomplishments: the animal’s work attempts to be exhaustive, and is existentially seized by this undertaking. It is more urgent than simple maintenance of territory. It is a mode of existence.

How to say

The end of Deleuze’s text is sublime, even if Beckett does most of the work. I struggled with the beginning of the second part; I think I need to reread it. But the end is very strong. Deleuze speaks there of how Beckett employs yet another strategy, once all permutations of an object or a gesture have been exhausted, as in Molloy: his strategy is to make words grow — or perhaps drift, in any case to make them proliferate — within sentences, in order to cause the meaning of those words to slip, not to enrich them, but rather to remove meaning, to exhaust significations, almost as if one were correcting a misunderstanding.

Grey Time

There is also a beautiful section in this text where Deleuze speaks of the insomniac. This is, once again, a beautiful — perfectly Deleuzian — way of setting aside the simple definitions of absurd, surreal, or strange often applied to Beckett’s work. Absurdity would be too much of a pastiche to describe his way of figuring existence — a kind of easy parody of the strange aspects of our lives. In Beckett’s work, one does not dream of “bizarre things”; that would be too easy. Rather, one is seized by a force that refuses to force, an event that refuses to happen.

The insomniac is very much in the world of reason, consciousness, and life, but in a modified state that transforms their capacity to act. The work — the artifact of the work, its form, its figuration — attempts to produce in us this here-elsewhere state, ex-stasis, outside-there, of its characters. Just as Waiting for Godot is a kind of play that — in its very title — struggles to begin, and never truly begins: one is always waiting for the beginning, in suspension, and that suspension itself is the work. The work itself is that suspension.

The other day, I told my psychoanalyst that Beckett had stated that, between the two versions Quad I and Quad II, 100'000 years pass. Laura Salisbury calls this, with a very beautiful title, Grey Time. The “grey” of this title comes from the anecdote in which, during the filming of “Quadrat II,” Beckett saw a control monitor used to calibrate cameras with a black-and-white image. Happy with this new perspective the image offered him, Beckett declared: “Between the two parts there is an intermission of 100'000 years”.

Being myself engaged, throughout my life, in a sustained struggle with various physical and psychological conditions revolving around insomnia, “restless syndrom” and other psychophysiological disturbances related to sleep, I told her that I had indeed known, without any ambiguity, in an absolutely factual manner, i.e. quite intimately, this grey time that lasts 100'000 years. That insomniac who painfully prolongs falling asleep for 100'000 years — that is me, every evening, for a lifetime of evenings.