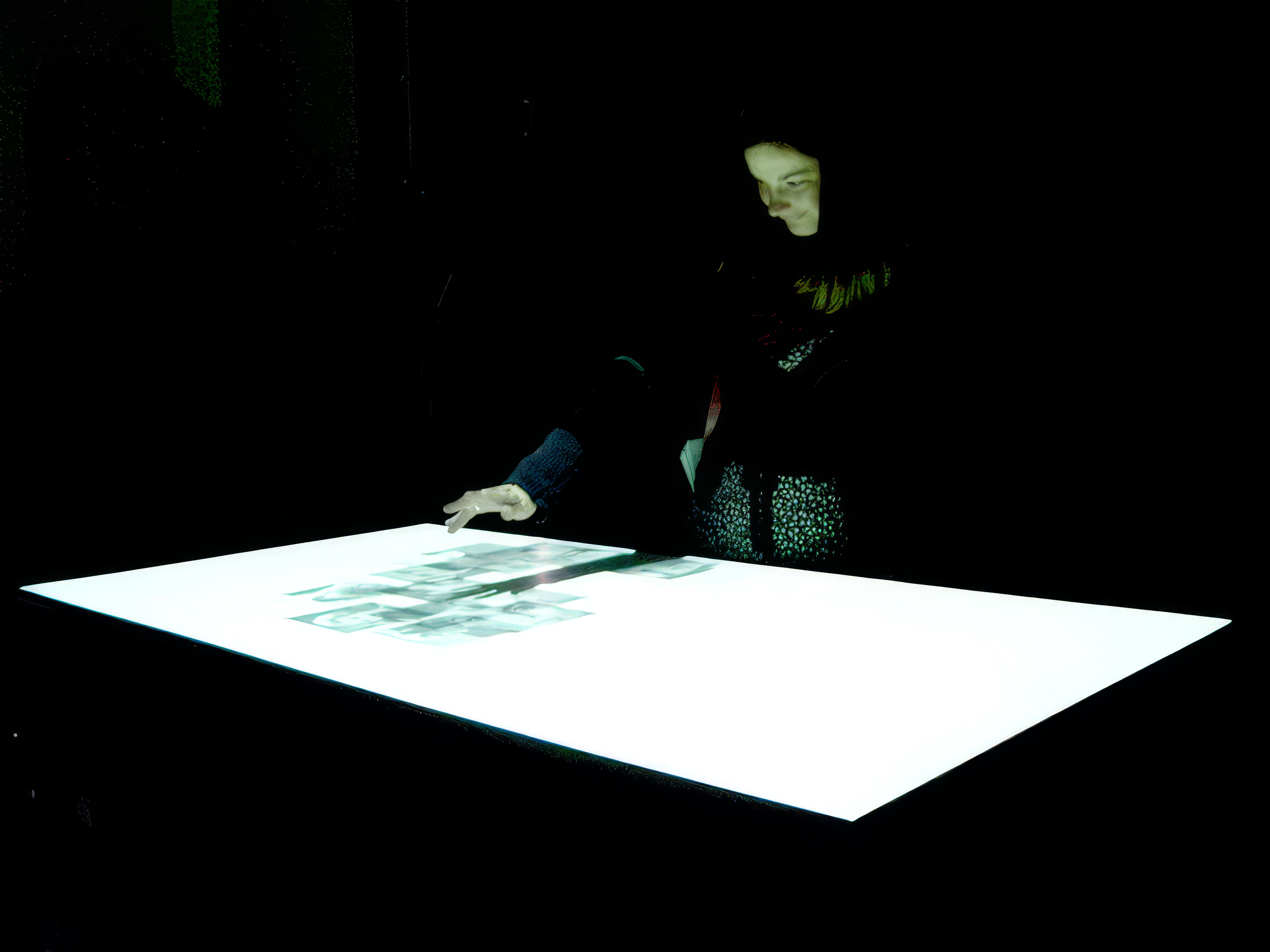

Concrescence is a software platform for the creation of interactive and generative cinema, coupled with an interactive Hypertable where users can intuitively interact with the film with the use of their hands.

- Concrescence

- Douglas Edric Stanley

- Generative Cinema Installation

This simple yet versatile machine brings together a creative software tool, a system for interactive and generatives narratives, and a physical apparatus for interaction — indeed, for the experience of the image itself. What is proposed is the creation of a genuine plateforme for interactive, generative, or non-linear audiovisuelles narratives — in other words, algorithmic narratives. The program addresses a recurring problem in the design of interactive narratives: the problem of choice. One frequently encounters a widespread assumption about interactivity — sometimes even among creators themselves — according to which certain forms of interaction would offer less “freedom” than others, and thus less interactivity overall. The flaw in this conception is that it confuses interactivity with choice. It amounts almost to a consumerist mode of thought, transforming the manipulation of images into a kind of image shopping, and in doing so missing the crucial shift toward a dynamic, that is to say programmed, image.

Interactivity must not be reduced to a limited set of choices (“yes,” “no,” “left,” “right”) in which the user is supposedly free to logically “choose” the destiny of a story. First, there are many well-known cases in which interactivity has nothing to do with choice, but rather with movement — an “axis of freedom.” Second, the supposed “freedom” of choice is illusory: interactivity is no more “free” than any other medium, unless one grants the user access to programming itself, in the same way that one might give children a pencil and a blank sheet of paper and teach them to write (cf. Smalltalk).

Moreover, in the case of interactive storytelling, choice is almost antithetical to narration, insofar as it prevents continuity in the articulation of elements — a continuity that is essential to narration. What matters is seeing how A becomes B, and then C, and so on, rather than simply knowing that A has become B — which belongs more to the realm of information than to that of narrative. Finally, an interactive narrative lacking subtlety in its handling of the apparatus, where the “game” of interactivity is overly explicit, is of little interest to us on aesthetic grounds: we seek the intuitive interface rather than the explicit one.

Explorer. My response to the interactive-choice model consists in creating the best of all possible worlds: offering the player an infinite range of possible combinations through the nuances of manipulation and movement, while granting the computer an equally infinite range of possibilities within the logic of narrative. The player can manipulate the images endlessly; they are “fully” interactive. The player can even alter the “editing” of the images, thereby transforming the very form of the narrative’s unfolding.

To engage meaningfully with this activity, the computer is given the freedom to propose one image rather than another. The computer organizes the structure of the narrative while the user transforms its expression. This model of interactivity is already familiar from video games: we freely control a character, for example, but we do not command every missile or obstacle that falls upon them. It is precisely this lack of total control over all parameters — over the entire system — that confirms the authenticity of the interaction.

From this perspective, one might say that in an interactive narrative what truly matters is the ability to influence the story, rather than to command it or create it outright. The manipulation we propose is both active and passive: it is neither entirely a matter of mastery nor entirely automatic. In this sense, it bypasses what we consider to be the false problem of choice.

Generator. To circumvent this false problem, Concrescence proposes a model based on generativity, in which interactivity influences the appearance of images without ever fully controlling them. The user remains free to interact as they wish, but the computer responds in its own way as well. In order to sustain this double play — to construct a narrative from unpredictable interactions — a narrative generator was developed to ensure continuity between elements. Its role is to observe the images that have already appeared and to propose new images based on the narrative elements contained in the preceding ones. The computer thus observes the manipulations and suggests continuations to the player.

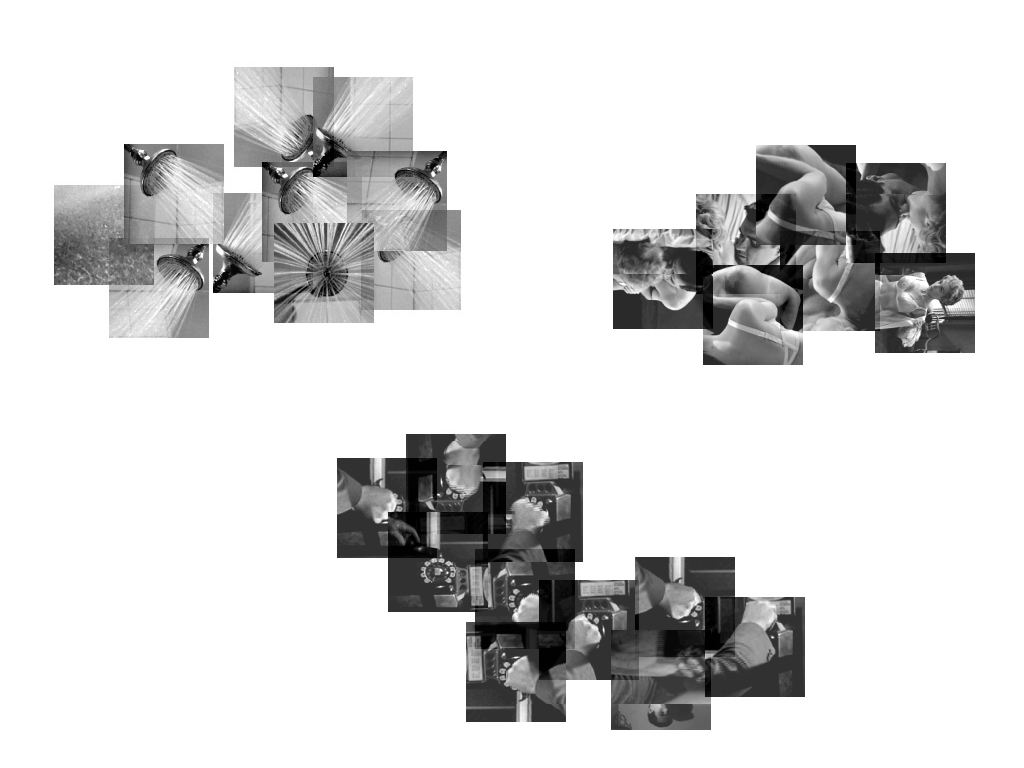

Ironically, the generator re-linearizes disparate data — but does so on the fly, in real time, within a combinatorial system that cannot be precisely anticipated. It is through this mechanism that we avoid the problems associated with choice and data branching. Narration is reintroduced in a more subtle way: each image is free to appear and disappear; the user may freely arrange, assemble, and manipulate them; yet a program oversees these associations to ensure that only images that are plastically compelling or narratively coherent enter into these assemblages.

hypertable. Beyond the need for new narrative structures — which necessarily entails the creation of new authoring software — there is also a need for new modes of dissemination for this emerging cinema. The frontal image of cinema, and even of interactive television, does not sufficiently account for the hand — that is, the body — of the player. Although “classical” cinema is far from passive, it nonetheless makes subtle interactions with the image difficult. The configuration of a body seated in a chair obscures the generative, evolving potential that an image constructed or manipulated by a computer can offer.

Consequently, we propose to reorient the image and make it accessible to the hand. We therefore propose an interactive projection table — a “hypertable” — coupled with our generative software: a table on which images emerge on a surface sensitive to human touch. The interest of such a form of interactivity lies in the fact that it offers a dispositif that is both familiar and novel for the body. The simplicity of this table lies above all in the legibility of the interaction: the image is placed directly within reach of the hand. The tactile table makes explicit the relationship between image and manipulation. The image is read with the hand.

The necessity of such legibility arises from a concern for the future of the moving image. Experimental dispositifs can only take us so far. We need concrete propositions for this emerging cinema: machines that a public can immediately grasp, in which already-acquired gestures construct a cinema that is at once recognizable and radically new. To allow intuitive interaction with the image and thereby avoid the logical manipulation of a “graphical interface,” the manipulation of the table of the machine Concrescence relies — just as eyes do in cinema or ears in a concert hall — simply on the most standard configurations of the body. As with cinema, theatre, or music, the interface must be the body. There is no contradiction between these two tendencies: faced with the increasing complexity of modular narrative structures, it is entirely coherent that new dispositifs of exploration and projection should become necessary.

Growth. Returning to the narrative program, one may note in passing that it is nothing other than an entity of artificial life. Even without interaction, this entity grows and declines — causing images to appear and disappear — according to behavioral rules of life and death (cf. Conway, The Game of Life). Without interaction, stories come and go, within a narrative temporality distinct from that of interaction.

The importance of employing a model derived from experimental biology stems from the need for the story’s autonomy with respect to the manipulator. The story exists independently of the manipulator; it is alive outside of them. By placing their hand on the table, the user causes images to grow, but it is the images themselves that determine their own coherence and existence. Each growth of images constitutes an entity with its own semantic coherence. By using a system akin to that employed by search engines in their analysis of the World Wide Web, this artificial life program allows only images that are semantically coherent with those already revealed to grow. Each growth is composed of heterogeneous images — randomly drawn from the database — but only those that produce harmony with the overall growth are retained. This independence between the two life systems — the hand of the manipulator and the artificial life system that grows around it — ensures the persistence of narrative under any type of interaction.

Growing the image. Connected to the table is a computer that analyzes the position of the hand and allows the Concrescence software to reveal images — to uncover them like fragments of hieroglyphs in an archaeological excavation. One moves one’s hand across the surface of the table, or lets it rest there, and images appear. More precisely: rapid, fleeting interactions cause empty frames to appear — mere image potentials; it is only by slowing one’s gestures, by involving one’s body more fully, that narrative images emerge. When the hand is placed on the surface, images grow around it, driven by the artificial life program that governs their growth and decay. From this initial growth, micro-movements of the hand extend the narrative expansion and allow stories to develop.

Each image in the narrative is a chrono-photographic image — that is, a photographic image in motion, containing its own set of images and its own temporality. The manipulation of these images can be both vague and precise: the manner in which images are revealed influences the arrival of subsequent ones and alters the narrative itself, which is constructed in an entirely discreet manner. A narrative grows and develops in contact with the hand and the surface of the table.

///////////////////////////////////////////

Concrescence is a software program for the creation of interactive and generative cinema, coupled with an interactive Hypertable where users can intuitively interact with the film with the use of their hands.

As a software program, Concrescence is organised around database of small, moving image fragments, a kind of infinite potential for non-linear narratives. As the program runs, images accrete -- hence the term “concrescence” -- forming a mosaic of images that are subsequently projected onto the hypertable.

The hypertable is a simple wooden table 160cm x 85 cm x 88 cm, onto which images are projected. Above the table, a surveillance system using various near-infrared filters and optics connected to a circuit board allow the system to “see” human hands as they move upon the tabletop. When a hand is placed on the table, the surveillance system distinguishes it from the table itself, and instructs the Concrescence software to grow images around it.

The images projected onto the table come directly from the database, but are filtered through a unique, but simple, semantic processor that limits “anything goes” accretion by allowing images to bond with another image only if there are conceptual relations between them. These conceptual relations are created by an author, using the integrated authoring interface. Images are placed visually with other images, and the system is told to “remember” their relationships (proximity, number, etc). The author can therefore design a narrative coherence for the subsequent interactors, while allowing the interactors to investigate various tangents and follow the narrative soup in their own time and manner. The entire process has been designed as both a cinematic narrative device and a more subtle interactive putty out of which non-linear narratives can be designed and caressed.

The questions explored by Concrescence revolve around the future of traditional cinema in relation to the possibilities emerging in algorithmic art.

One of the major contributions of Concrescence, lies in its ability to resolve the endless use of choice in interactivity. Interactivity is a rich medium, and should not be reduced simply to the offering of choices (YES, NO, LEFT, RIGHT) to a potential user. In fact, in the case of interactive cinema, offering choices is in many cases counterproductive to the construction of a narrative. By refusing the reduction of interactivity to choices, and instead opting for a more dynamic, plastic, playful articulation of the elements, Concrescence reintroduces the pleasure of editing to the viewer's experience of cinema.

As an artistic project, Concrescence has been designed for a specific author, namely myself. It is my soundstage, editing suite, and projection theatre all rolled into one, and I am currently using it to explore variations on cinematic narrative form.

Algorithmic cinema

While video software has introduced a new workflow, the result nevertheless remains, for the most part, tied to more traditional linear media such as video, television and film. And while the Internet has introduced new means of presenting, contextualizing, and even producing work, the idea of an emergent generative cinema has not been sufficiently explored. Beginning as a speculative software project, Concrescence began with an interrogation on what a non-linear cinematic authoring tool might look like from an experimental artist’s perspective. Several variations on this opening question resulted -- one of the more interesting being a dynamic VJ-ing program entitled The Object Machine -- but all of the variations come back to the same visual form: a mosaic of semi-autonomous video objects in which one moving image triggers action in the next image-object in a visual cascade of looping waves. This method allows for any image to potentially aggregate with any other autonomously -- allowing the computer dynamic associations -- and for the cinematic action-reaction editing of temporal composition to take place within the frame, rather than between frames. As the ensemble is no longer tied to any temporal necessity, the whole can move and evolve at varying rhythms, both according to the will of the interactor, and according the necessities of the generator. The cinema form becomes both generative and interactive, there is no contradiction between the two.

Additionally, Concrescence attempts to bring the body back into the interactive cinema experience. Rejecting complex physical electronic interfaces, I propose instead a simple corporeal experience in which the human hand shapes and explores an interactive audiovisual narrative through intuitive gestures. This simplicity is essential. The power of classical theatre-based cinema resides in its usage of basic body functions: sight, hearing, immobility. However diverse the semiotics of its contents (classical Hollywood narrative, French nouvelle vague, Asian kung-fu action-adventure), cinema always comes back to the platform of an immobile body before a audiovisually mobile projection. If interactive cinema is to “compete” with this model, it will need a similarly powerful simplicity in its use of the human body.

The first step was to detach the cinema screen from its pedestal, and reposition it at hand’s reach. This liberates the spectator from immobility, and allows her to “move around” the diegesis, passively observing or actively exploring, without having to leave the visual world to think about choosing the next scene. The frame remains mobile, but now it is both the interactor and the image that move, suggesting almost naturally the ability to “act” upon the image. Also, allowing interaction at any position on table, means that this user-mobility is free-form, and not tied to any predefined gesture.

The second step was the usage of a common evocative object: the table. In the past, I have used the floor, and/or all four walls, which instinctively evokes a theatre experience rather than a cinematographic one. By using a table, I can tap into the dual public-private nature of the table, its passive-active status. The Concrescence hypertable is at once an operating table, a writing desk, a work bench, a kitchen table, a café table and a screen. This familiarity makes the interaction very comfortable, reminds us of familiar gestures, and immediately places us into an evocative context. But whatever its evocations, the hypertable always implicitly suggests that something will be constructed.

The third step was the simplification of the gestures required to manipulate the dynamic cinema. To render evident a user’s interactions, immediate visual cues are given as to the location of their hands on the table’s surface: by mirroring the user’s presence, they know that their body is integrated into the space. This interaction, however, is purely superficial, and does not lead to the creation of new narrative material. In order to truly shape the experience, the user must slow down their movements, further implicate their body into the experience, only then will the interface truly respond. By using body presence, rather than symbolic gesture (point and click), interactors are subtly forced to – much like the cinemagoer as she eases into her chair – enter into a lightly modified environment. In fact, one can move in and out of this gestural slowness quite easily, back and forth from spectator to interactor, unlike the cinemagoer that must radically shift environments when leaving the chair.