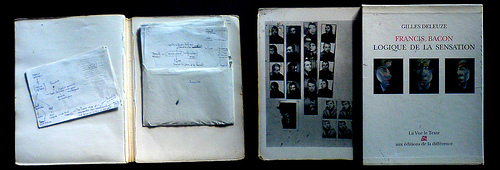

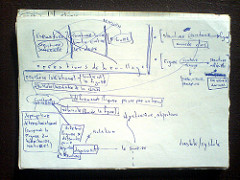

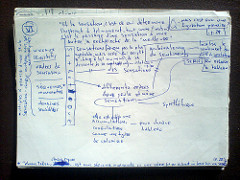

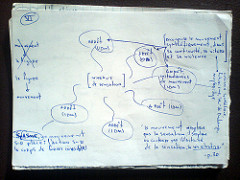

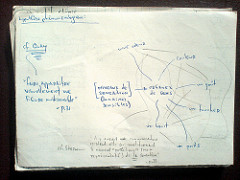

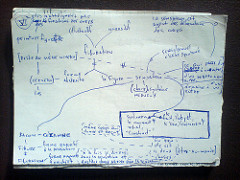

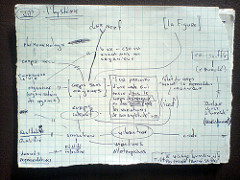

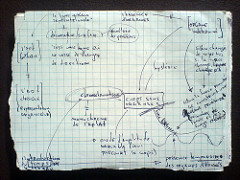

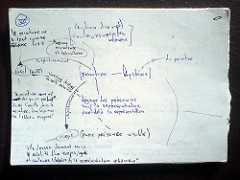

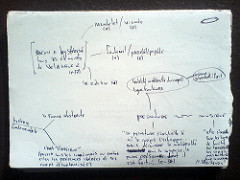

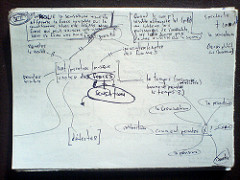

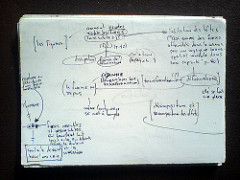

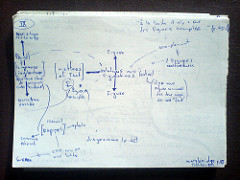

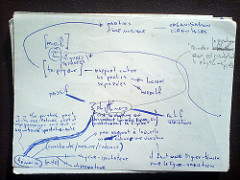

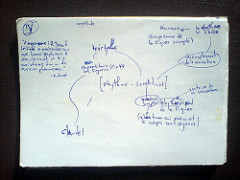

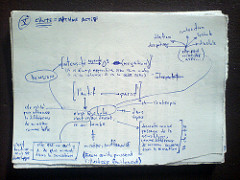

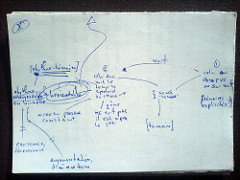

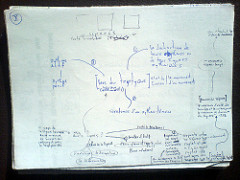

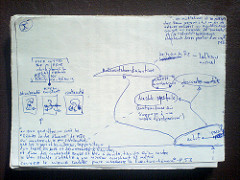

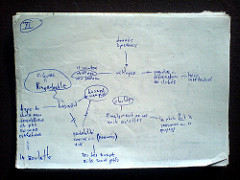

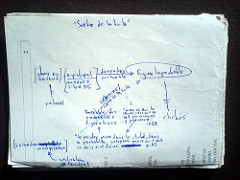

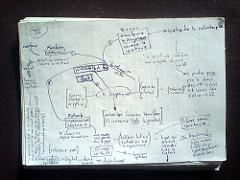

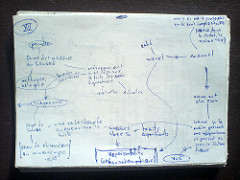

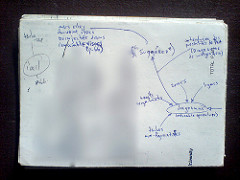

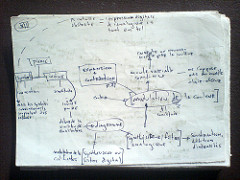

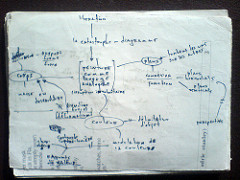

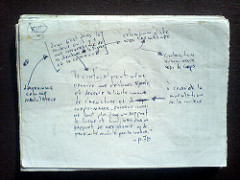

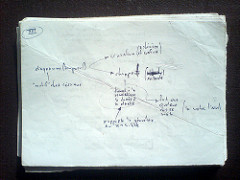

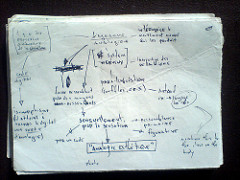

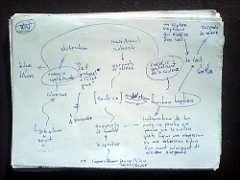

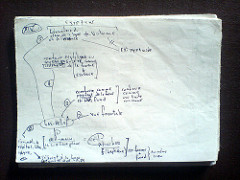

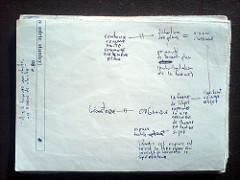

I was working on Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the « egg » this afternoon when I stumbled upon this cachet of notes I had apparently stored at the back of my copy of the 1981 edition of « Logique De La Sensation ». They revealed a series of conceptual diagrams I had made of each chapter of this amazing book.

I had totally forgotten these notes as they were part of a project I had to abandon for legal reasons. Basically what happened was the copyright holders at Bacon’s estate turned out to be just too darn stuffy to work with. At the same time the French publisher was being equally difficult. Deleuze was too sick at the time to be troubled with getting his editor to open up his book (he was coming out of yet another failed lung surgery), so I had a doubly impossible situation. If I remember correctly, Deleuze threw himself out of a window to end his physical suffering just about the time I was trying to get this project off the ground, which pretty much hammered the last nail into the coffin of this project (yes, that’s an intentional bad joke, but one should always show irreverence for one’s heros ;-). So I moved on to other things and eventually forgot all about the 12 months I had put into this project. Until I found these little notes.

There should be some digital documents and software lying around, as I just recently re-arranged a whole library of CD-Roms of the dozens and dozens of failed projects I’ve explored over the years.

What I find fascinating about this book is the quality of Deleuze’s portrait using the pigments of philosophy. Rather than building a philosophical treatise on the possibility of painting or the ontology of artistic practice (yawn), Deleuze instead focuses his magnifying glass (and scalpel) onto the Bacon-machine itself as his object of study. This makes the entire endeavour more intimate, because it requires moving into the working of the machine itself and seeing how it functions. Hence the « logic » of Bacon’s art-production-machine, which is to be understood more as its blueprint, or diagram. Indeed the logic of the « diagram » is essential here not only in his description of Bacon’s re-invention of perspective, but in terms of Deleuze’s method of analysis itself. (Even a cursory glance at my current theoretical work should show the influence this method has had on me).

Unfortunately, the re-prints of this book make it difficult to follow his analysis of the paintings (which are quite in-depth), as there are no longer the same plates he referenced in the original edition. But it’s still worth it. His chapter on « athletics » and « hysteria » is worth the price of admission alone, with or without the pretty reproductions. And if you’re interested, I stole my concept of « éffort » from those two chapters, although I somewhat re-worked them for the then-popular context of interactivity (re-yawn, snore). Therein the recurring idea I have worked with for years to describe interactivity — that of extracting from production the object produced and seeing what remains —, can be localized in those two chapters of Logique de la sensation, although somewhat more implicitly than explicitly. And I love the way he alludes to Kafka’s famous quote on swimming: « I can swim like everyone else, only I have a better memory than them. I have not forgotten my former inability to swim. But since I have not forgotten it, my ability to swim is of no avail and in the end I cannot swim. » This refusal to master swimming (or productivity in the case of interactivity), to retain a lack of mastery in mastery, is a powerful idea for artistic practice, even if it does risk sounding a little too cliché (I’ll take that risk, thank-you-very-much). Whatever the case, in Bacon’s paintings the idea is perfectly appropriate, because indeed the figures are in a constant state of making figurative that which desires formlessness. And finally, this was one of the ideas that finally cured me of any residue of 80’s postmodernism, and opened up a whole series of artistic methods for me personally.

And while I’m rambling, it just occurred to me that my last admission might explain the distinction between my own position on artistic activity, and those of many of my colleagues who emerged from more official channels of art education, steeped as they are in a sort of negative-dialectics of the Kantian sublime. That’s a mouthful (and a pretty nasty accusation now that I think about it), but a pretty accurate mouthful that I am perfectly willing to stand by. I remember quite a few debates with some very heady artists at the time I was working on Logique de la sensation who complained of Deleuze pulling art back down into the morass of sensation and perception, and basically re-pictorializing art, or sending it back the way of impressionism. I actually agree with them, and cringe at a few passages in What is philosophy? wherein D&G limit art to the production of « percepts ». But I still retain that art has throughout its history had an intimate relationship with plasticity, form, figuration, landscape, portrait and what-have-you, even in the midst of the peak of 60’s and 70’s conceptual art. Sure, it’s hard to see much of a political position in Bacon’s refiguring the defigurative — without sinking into some lame ode to the arts as the last form of political resistance —, but who the hell needs an all-encompassing definition of art anyway?

As a philosophical treatise, La logique de la sensation (« The Logic of Sensation ») was not one of Deleuze’s massive cultural bombs such as Difference and Repetition

, and his books written with Felix Guattari: Anti-Oedipus

, Mille Plateaux

(A Thousand Plateaus

), and What Is Philosophy?

. In those books, seminal concepts such as the rhizome or the corps-sans-organes are introduced. In contrast, The Logic of Sensation is a smaller book, less ambitious than those works. Logique de la sensation would never have the global influence that those books did, nor did its concepts dislodge themselves from the book and travel about in the cultural landscape like so many little memes. This is not to say that Logique de de la sensation does not invent important concepts — to the contrary, the book is an endless stream of inventions. The aforementioned concept of « éffort » would probably be the most important offering from this book, as well as the concept of the chute, which I used at the time of Deleuze’s death to comment its « critical reception ». There’s a beautiful section on animality and the becoming-animal. And finally, there is a significantly different version of his concept of the « diagram » from the version he proposes in Foucault

. So there is some important writing here for people working outside of the field of painting, or art for that matter. What I mean to suggest is that this is a minor work that creates it’s own territory that works on you locally, albeit intensely. It requires its own study, and yet reads like an enthralling novel. It’s the difference between Nieztsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra and Zur Genealogie der Moral : the former you read on a road trip, feeling like Jack Kerouac — worldly with your Bildungsroman half-torn and dangling out of your rucksack; while with the latter you actually learn something, and have to sit down in a small well-lit corner and let the thing soak in.