Standing before a work such as Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion’s “Dérives”, spectators will perhaps experience a certain sensation of disorientation, of floating adrift. In the work, 2,000 images of water, excerpts from throughout the history of cinema, are edited by a machine into a single continuous sequence: an endless film. This film contains only one central character: the image of water. Excepting power failure, the film never ends, preferring instead a slow deceleration into moving images of ponds, of puddles, or a glass of water, before transforming into tears, mist, a light drizzle which eventually breaks out into a downpour, leading to thunderstorms, hurricanes, shark attacks, and tsunamis before calming back down into a light stream of images and then starting all over again. It is a constant ebb and flow, without end, that rises and falls like the tide; an endless film that is always the same — a film about water — and yet which can never be exactly the same: a fluid-film flowing straight out of the fragments of Heraclitus.

It is easy to be swept up into the pleasures of the spectacle in a work such as Dérives. Its form allows us to permanently oscillate between recognition and anticipation: a sort of name-that-sequence game wherein we try to identify each one of its famous and not-so-famous sequences, mixed in with a certain feeling of anticipation as we wonder what next image will carry the wave on its journey.

As for actually attempting to read this wave, i.e. to dive beneath its surface and to observe its construction from within its depths, the exercise is far more perilous. If we start with the 2,000 images, we quickly realise that this database is nothing more than a cloud of disparate points. Nowhere do we find this wave, this flow of water with its internal movement; instead we find nothing but a collection of drops. For, in reality, the work is far more than a simple collection wherein one need only to collect a series of images in order to capture the “image” of water in all its states. Indeed, there are 2,000 image sequences that together make up the work; but it is not enough to reunite 2,000 sequences alone in order to compose a work such as Dérives. Hence a drunken sense of disorientation before a flow of images that we appreciate on an intuitive level, without being able to fully identify its origin.

“Mr Palomar sees a wave rise in the distance, grow, approach, change form and colour, fold over itself, break, vanish, and flow again. At this point he could convince himself that he has concluded the operation he had set out to achieve, and he could go away. But it is very difficult to isolate one wave, separating it from the wave immediately following it, which seems to push it and at times overtakes it and sweeps it away…” –Italo Calvino, Mr Palomar

When spectators are informed that the film they are watching has been “generated” by a computer with a dedicated algorithm, their first reaction is often to ask if the result has been “programmed in advance”. If one where to reply no, the algorithm varies the film endlessly, the spectator often concludes that the process is therefore “purely random”. As if it is perfectly natural, even necessary, to oppose “programmed” (i.e. “predetermined”) processes and “random” (i.e. “undetermined”) processes. But just such an opposition would never work in the case of Dérives, whose operating principle is to create a sole and unique film, always coherent, while navigating within a fluctuating collection of images that never produces the exact same result. In other words, a purely “random” film would be nothing but incoherent juxtapositions of sequences that had nothing to do with each other, a cacophony without much artistic value. This is clearly not the case of Dérives, for whom the sinuous juxtapositions of images are not only logical, but also full of an undeniable poetic and emotional force. On the other hand, a film created by an entirely “predetermined” program, i.e. wherein the machine would have no room for autonomous action, would harken back to a classically linear film, more or less edited “by hand” with a sequence of images more or less determined by its creator in advance. This is clearly not the case either, given that this flow of images named Dérives will never be exactly the same sequence of images.

The difficulty comes from our inability to perceive the rich interaction of simple elementary particles (the images) and the process which reunites them into a common purpose (the image). If, perhaps inspired by Mr Palomar, the spectator attempts to analyse each algorithmic edit separately (sequence A > sequence B), he or she will miss the algorithmic ensemble which constructs the film over time. This larger sequence can only be observed as a whole, which ironically means in the role of a classical spectator of cinema allowing him or herself to be swept away by the image.

“While our senses respond to everything, our soul cannot pay attention to every particular. That is why our confused sensations are the result of a variety of perceptions. This variety is infinite. It is almost like the confused murmuring which is heard by those who approach the shore of a sea. It comes from the continual beatings of innumerable waves.” –Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, “Discourse on metaphysics”, §33; Montgomery, George R. & Chandler, Albert R., translators.

In its natural form, as in the program conceived by Emilie and Maxime, a wave is composed of a multitude of different components, interacting on multiple levels and all at once. The global form emerges from the complexity of these individual interactions, hence the sensation of an intangible perception: the “confused murmuring” of which Leibniz speaks, and which cannot be perceived outside of an emotional affect, both intuitive and all encompassing.

For the author of an algorithm, it is often impossible to write the program in one single stroke, especially given that the complexity of its final output makes it all too difficult to orchestrate via some masterfully rationalised architecture. Nevertheless, a computer program must be executed within the constraints of the machine, which requires for its part both explicitness and rationality. There is no room for ambiguity in the machine, for whom such an ambiguity can only lead to a refusal of execution:

“error: call of overloaded ‘function(type)’ is ambiguous”

How then does one write just such an algorithm — at once subtle and evolving, i.e. generative — within a materially determined assemblage with its language of explicitly rational constraints?

The solution lies in the orchestration of individual interactions of each drop, but multiplied up to the scale of an ocean of possible droplets. This technique of using the singular, only propagated to fill a field of possibilities, is precisely one of the internal logics proper to computer programming. It is a method for treating a great number of data points individually, but all at once.

There is a table of values at the heart of Dérives which describes the possible interactions of all the images contained within the work. It is a list of keywords and values arranged in categories and which allow for the establishment of a general framework for the different narrative, logical and aesthetic possibilities for the images. It is a table of values cross-referenced with each and every image. In the category “divisions of water”, for example, we find values such as “unitary mass”, “numerous droplets”, or “rain”. Through such a description we can begin to see a certain distinction made between two complex ideas of “unity”, along with the transition that might lead us from one to the other: ocean and rain are two opposing forms of water masses, opposed precisely in the manner in which they gather their internal elements. By explicitly describing this opposition and the transition between them, the machine can then deal with such subtleties much more easily. Each of the 2,000 images is described to the machine in this fashion, image by image. This category, “divisions of water”, is more or less factual, as are descriptions of “weather” or of “light”. They allow for the program to understand characteristics of the images that are more or less objectively perceivable by the spectator. But we also find other, more subjective categories, such as those of “hedonism”, which describes images to the machine on an entirely different scale of measure. This category, along with descriptors of the level of “tension” within the image, allow Emilie and Maxime to reunite images in a far more subtle manner, on the level of sensations, all the while making them readable to the machine. From these descriptors they can then run a series of routines that string together images in sequences that progressively increase the “tension” until a certain level of “hedonism” is achieved. By multiplying these criteria and running them in parallel, the result is made far more complex without having to play off of one and only musical cord. It is a subtle dance of sine waves, flowing in and out of interactions between several simultaneous criteria which, individually, are linked together linearly but which collectively make possible a more complex form: a wave of images.

This central table of Dérives — these descriptors of the internal forces of the images — is a lot smaller than one might think: not more than about twenty categories. And within each category there are very few levels of variation: usually two or three, sometimes a little more, but never growing beyond a dozen. For it is not in multiplying the number of categories that such a table will somehow improve the “generative” qualities of a work. To the contrary, it is precisely the reduction of criteria to their strict minimum which gives Dérives its force as a work of art, allowing it to dance a fine line oscillating delicately between the chaos of a tsunami and the calm of a sleepy riverbed. Too many criteria would push the work to the edge of entropy: a chaos similar to a film edited by the roll of dice. And too few categories would force the film into an all-too-predictable form: a sort of mechanical loop of the same repeating themes. It is in this in-between state where we find the internal current of the algorithm, wherein the film is always at the edge of change while retaining coherence and a sense of logical progression. It is at once discernible, perceptible for the spectator and yet impossible to fully grasp, impossible to put put our finger on the exact nature of the image which would allow us to freeze the wave in one single frame.

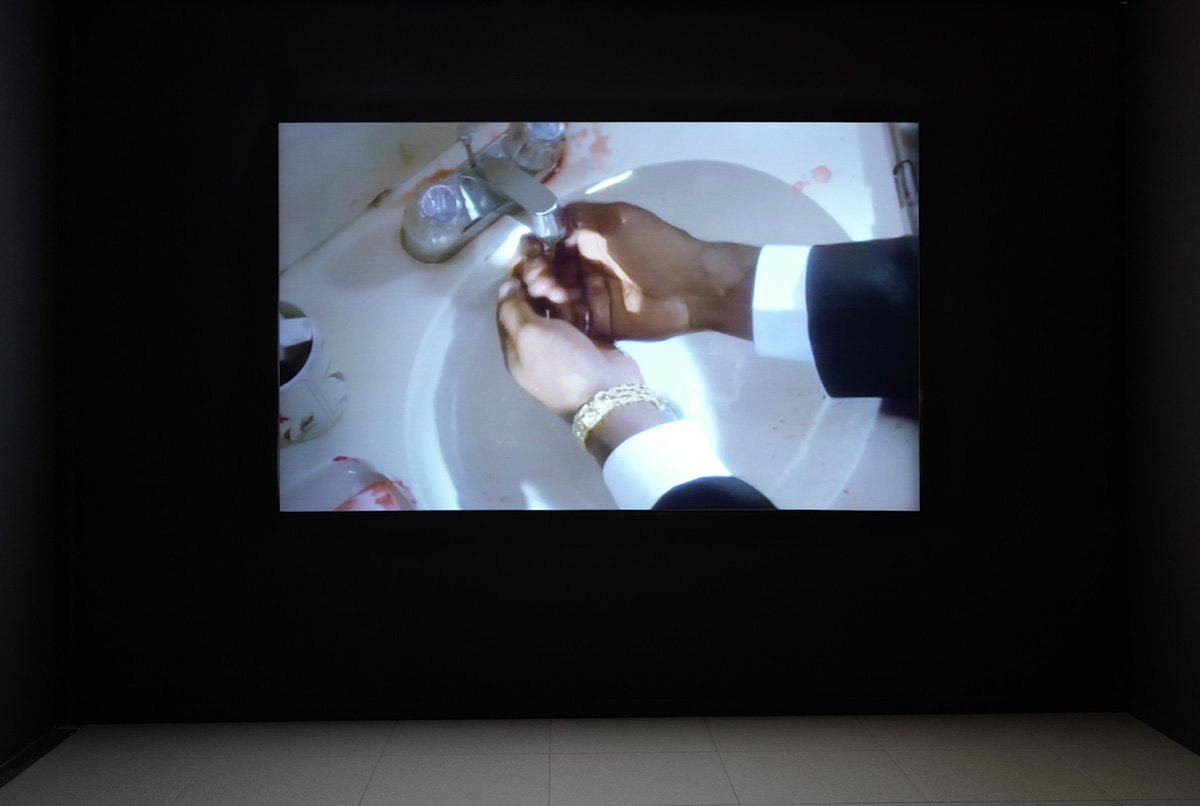

As we let wash over us this dance of differing and deferring criteria, generated in an undulating movement of the program which is also that of the image, the spectator enters and exits the image as they please. Given that the program theoretically never stops, Dérives has no “duration” in the classical cinematic sense of the term, i.e. a time delimited by the physical beginning and end of the media device. Nevertheless — and this is the case with any film —, there is yet another “duration” which emerges from the image: the duration generated by the consciousness of the spectator. Just as in Bergson’s description of sugar dissolving in a glass of water (here held by Mia Farrow or Emily Watson) and the time it takes to dissolve, each and every spectator drinks these images in their own manner, as if they were destined for us individually. Dérives is this particular scene: each and every spectator perceiving their own specific moment within the ebb and flow of an image generated here and now, before our very eyes, just for us, and yet which does not stop for us either. By following the movement of the algorithm we are perfectly capable of perceiving the logical transitions from one sequence to the next, and even of understanding the criteria which unite them; and yet incapable all the while of freezing the image as a whole and observe all its interactions in a rational unity. Our consciousness enters and exits this current while the ebb and flow of the image remains quite objectively within its own logic and its own temporal existence. A play, algorithmic in its nature, of the rising tides of images and of the image. The misty image of a wave, a vague, floating image, or, as one can only say in French, une image vague.