Ok, let it hearby be known that if one more person cites Picasso’s “Je ne cherche pas, je trouve”, they will be shot.

So I ended up speaking last Thursday at the Assises Nationales des Écoles d’Art. If you don’t know what that is, here is a post from a few days back (Assises Nationales des Écoles d’Art). Ohmygod, who the f##k came up with the idea of locking into a large conference hall a couple hundred french artists and intellectuals!@#¡¿? Actually, I found the whole experience pretty comical, and in the end damn cool to see how firey the whole thing could get and — gasp — passionate. But, as with many things French, the passionate side reveals a darker intrigue, mainly what in French is called le brassage de l’air, i.e. waving your arms about and making lots of noise in order to merely displace the oxygen in the room. Usually one displaces air in order hide an ulterior motive, namely to maintain the status quo. For there was sheer terror that could be felt in that room, sheer terror at the very idea of … change.

In our section of the Assises, we were supposed to be discussing research, and the official introduction and defense of research within our art schools. It might be worthwhile to contextualize that, for the introduction of this debate on “research in the context of art schools” is highly charged politically. There are several versions of the story on why we’re discussing research at this particular juncture, but I see three.

The first is simple : Europe has just introduced a new diploma standardization (that’s what Europe does : standards) requiring all higher education to enter into the logic of “Licence, Master, Doctorat”, 3/5/8, or “LMD”. And in order to meet this standard, curiculum has to be defined and credits have to be assigned according to concrete teaching-hours. Since what is actually taught in an art school is so experimental, and some would say (although we should be careful with this) obscure, French art school teachers are terrified and running around “ with their hair on fire®™ ”. The mere idea of writing down what they teach is for them the ultimate insult, as they see it as a judgement on the quality and quantity of their teaching. Recent fallacious accusations from idiots in our local city government would actually justify this fear, as would the official reasons cited by the mayor of Perpignan in his recent decision to close that city’s art school. Arists/professors also see it as the first step in the standardization of the subject-matter itself, followed by the sectioning-up of French art schools into various niches, i.e. instrumentalized art trade schools.

Leading us to the second reason I see for the current debate on ”research in art schools”. And this one is interesting for me because I can go either way on this issue, depending on how you frame the debate. On one side, when French politicians speak of more ”visibility” for French art schools, they mean more “applied” activity, populist, and “closer to the people”. It‘s demagogy, and of course bullshit. What they want is to instrumentalize art schools, and in their dreams at least, pander to the voters’ desire for immediate and short-term satisfaction. The result would be catastrophic and implode, but it’s what they desire, because they don’t understand long-term thinking. But that said, there is some truth to the idea that art schools should interface better with the larger community, and I would even say, the growing socio-economic context of the new millenium.

The final issue, a positive one, is the possible collaboration between art schools, universities, research labs, cultural groups, and private industry in the context of “new media”, i.e. digital media culture. This one is a no-brainer, because everybody wins. It’s also not a new idea (except for the French, of course). Industry discovers new ideas and unimagined publics; Art Schools find new sources for funding and even new technological artefacts, methodologies, and collaborators; and universities get their hands dirty with a pragmatic just-do-it (or production-based) approach that only an art school can provide. It is also a dangerous proposition, of course, hence the need to debate this issue seriously and develop strong protections for the smallest link — art schools — but a fascinating one, a constructive debate if you will. I have rejected publicly, and on several occasions, the idea of “interdisciplinary” art-science research. It’s a top-down model, and totally misunderstands the pragmatic and productive nature of artistic activity. But I debate this issue, as well as the problem of industrial forms of instrumentalization (we’re sandwiched between political and industrial desires to instrumentalize us), as a “chance” for art schools, and a possible new form of interfacing art production of the emerging digital culture. And nothing says that we have to interface only with industry when we get out of the education/museum context. We could work with political groups, foundations, etc., and develop art-technology projects with them. The “chance”, which can also been seen as an “excuse”, is the accident that happened to art with the introduction of computers and modular networked machines into its pratice. In other words, we are, thanks to the strange new artifacts before us, being offered an excuse to ask questions that we are not usually asking, and to collaborate with people we would have normally avoided. The desire for legitimzation is temporarily held at bay, just the time required to allow a new field to emerge.

This is of course already the freedom of art schools, and it is truly the beauty of the system; I have seen it in Aix : the patience they afford me to experiment with new questions, just the time required to develop a new field for the atelier, just as we have done with Antonin Fourneau with Gameboys or Pierre-Erick Lefebvre with our strange version of Rock n’ Roll. How then could this model be opened up for political groups, industrial partners, university and scientific researchers, without at the same time instrumentalizing the art school, politically and/or economically?

This is the question I tried to ask at the Assises Nationales des Écoles d’Art. I even asked these very questions at the round-table they invited me to, dedicated to the question of “déplacements”, or the displacements of art schools into foreign territories. And what response did I get? None. A Big Fat Silence. In fact, the forum quickly knee-jerked itself, and fell back to the brassage de l’air that had caracterized the two round-tables before it : art schools are great, we like things the way they are, we don’t need the LMD because we’re art schools damn it and to hell with you if you want to understand whatever it is we do. In fact, it even got worse : it was suggested during my round-table, as had been suggested earlier, that universities are looking to swallow whole the French art schools (perhaps, I have no data either way), even that Nicolas Sarkozy wants to shut down the entire Ministry of Culture itself, and that the big bad enemy is not only the Ministry of Culture but the Universities that would like to eat our budgets (a joke if you actually saw our budgets). Don’t get me wrong, I think there is some truth to these fears, and we have to remain lucid about their possible reality — but I am now convinced just as strongly that maintaining the status quo is precisely the best way to make these conspiracy theories a reality. Obsessing about the university system is perhaps the fastest route to bringing it upon ourselves. If we spend our time screaming that the sky is falling, someone might indeed profit from our distraction and eat our lunch. This is not the way to take an issue head-on.

The frightening thing about this detour from the debate-at-hand was the momentum it built up within the Assises, and resounded as a sort of intellectual mantra at all levels our discussion, squelching anything else. Frightening, because it was proposed by representatives of the university system, but terrifying above all because the force of their arguments were built precisely using the force of the University Verb. Arguments, screaming matches, ironic jokes, and off-colored remarks made by artists were mostly that of the manifeste, a certain political stance or artistic ethical position. The university intellectuals, on the other hand, were more sophisticated and used to their advantage their institutional superiority at manipulating the verb, the citation, and the dialectical structure. Hence it was via influence that they tainted our discussions, and led us ironically into a tautological closed-circuit argument on why it was we should avoid the institutions that formed them. This had the effect of a tornado where calm could only be found at its eye, staying close to the mantra (“confiding in the university is like giving your car keys to someone who wants to do you harm”) for fear of being pulverized by anything outside of this central core.

I also spoke of recent difficulties we’ve encountered trying to find out how to negotiate with industrial partners. Open source? Patents? Restricted use? Public domain? Sure, we can negotiate these issues one by one with our partners. But what sort of political platform exists to protect us during the negotiations (for all negotiation is a question of correctly assessing and amassing force)? I also spoke of the juridicial void as to how we can actually get this money into the school once we’ve signed these ellusive contracts. Does the money come directly to the school? No, for the moment. Does it go to a non-profit? This is apparently illegal, even if many do it. Et cætera, et cætera. Can I get paid overtime, or as a supplement to my current teaching, in order to work on these projects? No, for the moment. So we’re in a legal void.

But did this interrest anyone in the forum? Nope. Well, actually, after I railed at this general inertia, and eventually stormed off stage, quite a few people came up to me in private to express their support, but only in private of course. Hence the “Great Schism” : those that want to move French art schools into new territories, and those that see it as a form of active-minoritizing force that needs to be protected as is, as an a-topos or heterotopia (cf. Foucault). Strangely enough, these two positions are not incompatible, in fact one might even require the other, only in different strategic contexts. But we’re not there yet.

Research in art schools, some sort of political protections and economic means for us in these wonderful institutions we so desire to defend? New perpectives opening up onto critical uses of the powerful but frightening new social model? I guess that’ll be for some other day.

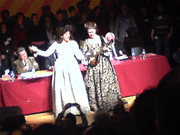

Here’s a crappy photo I took of the best moment, when two young students appeared onstage and sang our various manifests back to us in full royalist garb and manner. They were flanked by all the art school students who had also made the effort to come to the event (and were left silent, by the way).

On a happy note, I was given a lovely room at the last minute at the Hôtel de némours. If ever you’re looking for a nice place to stay in Rennes, this is your spot. The interior was apprently redesigned recently by a belgian architect, and reminded me of a pleasant stay at the Clift Hotel in San Francisco, but cheaper (since I didn’t pay for it, but also because it’s cheaper ;-). Usually hotels are so amazingly ugly that it was nice to see a simple adjustment to a typical small european hotel come out so nicely.

Why am I speaking about some nice but minor hotel when there were more important issues at hand? Well, you have your answer right there.